Parallels of the Holocaust (and Other Atrocities)

palestine, lebanon and israel's genocidal campaign ☼ decolonizing the mind as a form of resistance ☼ thoughts on human nature

What is human nature? I ask myself this question as Israel launches another genocidal campaign in the Middle East. The fact that “genocidal campaign” can be preceded by the word “another” without igniting a reader’s shock is emblematic of the crisis we are living in, one where Israel has slaughtered civilian populations with the material (weaponry, capital) and political (legislative, silence) support of the United States and the European Union. Some may view the descriptors “genocidal” and “slaughtered” as subjective, preferring headlines that paint Israel as a reactor, as opposed to the oppressor. While the rhetoric around Israel’s war crimes can muddle the narrative, the numbers cannot: 134,000 Palestinian people have been killed since 1948—41,000 of which were killed in the past three years (and counting); 17,825 Lebanese people were killed in Israel’s first invasion of Lebanon in 1982—and another 2,000 were killed in the past year alone; an estimated 4,000 to 5,000 Israeli civilians have been killed in the conflicts with Palestine and Lebanon since 1942.

The word “complex” is often used to reduce Israel’s war on Palestine—and Lebanon—into something that cannot be characterized by facts: that this war did not start a few years ago but in 1948, when leaders of the Zionist movement established the State of Israel and forcibly displaced 750,000 Palestinian people, a violent and destructive act that uprooted two-thirds of the Palestinian Arab population and destroyed over 418 villages. That this catastrophe, referred to as the Nakba (literally translating to “catastrophe” in Arabic) never ceased, continuing with the displacement of another 300,000 Palestinian people in 1967, the ongoing xenophobic refusal of the right of return for over 5 million Palestinian refugees, the institutionalized discrimination of Palestinian people via the 2018 Nation-State Law—which declares the right to national self-determination as "unique to the Jewish people", and the continued ethnic cleansing of Palestinian communities from East Jerusalem via forced evictions and property demolition. That the satellite data and spatial analysis of Israel’s recent military attacks in Gaza reveal a deliberate focus on civilian infrastructure (bombings of healthcare facilities, schools, and water infrastructure), characteristic of Israel’s unwavering commitment to dismantling the civilian population's ability to survive. That the same thing is happening, now, in Lebanon.

It is not very complex: The genocide we are witnessing is a continuation of settler colonialism. Israel plans to wipe out the indigenous populations of its neighboring countries to expand the State of Israel. The target is not terrorism but the civilian population; the goal is not military or economic control but demographic transformation. Repeatedly, Israeli officials have vocalized their desire to wipe out the people of Palestine and Lebanon, referring to civilians as animals.

The fact that we are witnessing genocide—with what feels like little to no control over stopping it—makes me question human nature. There are my friends and family who see the same things I do. There are the comments on YouTube, Instagram and TikTok that turn my stomach sour (“give back the hostages first!”). There are the friends I have lost to frantic accusations of antisemitism, as if, at some point, antisemitism and anti-war became synonymous terms for anyone attached to Israel. I like to think that, eventually, everyone will look back on these years, days and months painted with death and say “Never again.” Of course, that is not enough. That is barely anything.

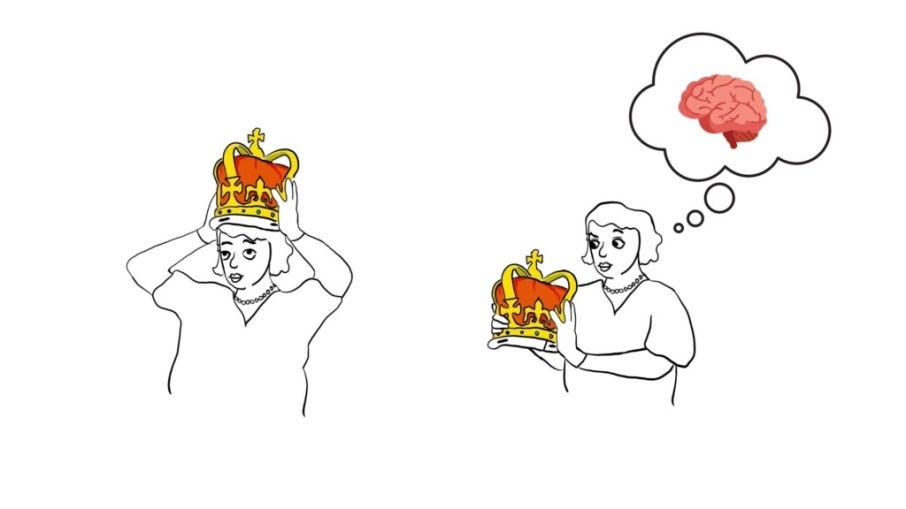

While human nature is still up to debate, the nature of history is not. The nature of history is premonitory. Many parallels can be drawn between the genocide in Gaza and atrocities of the past.

Israel is, in effect, creating a second holocaust.

The rhetoric and actions employed by Israel bear uncomfortable similarities to those used by Nazi Germany. Israeli officials describe the Palestinian population with dehumanizing language, portraying them as an existential threat that must be subdued at any cost. The concentration and destruction of Palestinians in the Gaza strip, with limited access to basic necessities, resembles tactics used in the Holocaust, where Jewish populations were placed in ghettos, isolated and deprived of basic rights. The blockade of Gaza, restricting the movement of people and goods, has led scholars to label the area a "concentration camp"—an echo of the atrocities we know too well.

Israel’s brutal methods of control, destruction of civilian infrastructure, and mass killing are not novel strategies. They are learned—notes from other times: Nazi Germany, Lyndon B. Johnson and the Vietnam War, Japan’s Occupation of Korea. The justification of bombing civilian areas on the grounds that the enemy hides amongst them has been used to legitimize widespread murder throughout history. The same goes for the strategic impoverishing of civilian populations (see: stripping of land rights, forced evictions, mass displacement) and demolition of key infrastructure.

Perhaps the most dangerous are the words. Posing another population as an "existential threat" is the default cry of a state that intends to wipe out that population by force. Israel has published a variety of media that paints Hamas and Hezbollah as pervasive forces that threaten the State of Israel itself, and that are, for military purposes, indistinguishable from civilian populations. All of this enables the IDF to bomb civilian areas on the grounds that they are liberating those civilians from terrorists, despite holding the sole responsibility for over 50,000 civilian deaths across both Palestine and Lebanon (a conservative estimate from OCHA and UNRWA). These textbook claims—that the IDF is “protecting” the State of Israel in its genocidal campaign, that the United States was “protecting” democracy in the Vietnam War—are guises used to justify mass death. The construction of the "enemy" in the collective consciousness—whether Palestinians in Gaza, people in Afghanistan, or elsewhere—is a colonial tactic used to frame indigenous peoples as "barbaric" and in need of "civilizing,” making acts of violence against them more palatable to the public, effectively framing (and hiding) genocidal campaigns behind illusory narratives of necessary defense.

Understanding these parallels are crucial for holding any state accountable for actions that perpetuate mass violence, and for ensuring that “Never again” applies universally, without exceptions based on political alliance, a concept that is foreign to the United States government.

America’s support of Israel’s war is intentional. It is also profitable. Since the end of World War II, the U.S. has provided over $318 billion in financial and military aid to Israel, establishing Israel as a strategic ally for maintaining regional influence in the Middle East. The U.S. military-industrial complex profits immensely from conflicts of war, whereby the continued sale of arms not only profits defense contractors but also perpetuates a system where militarization is prioritized over human rights. It is not just the United States: EU nations like Italy and Germany facilitate the continuous supply of fuel, weapons and parts for military vehicles that Israel’s military needs to maintain large-scale military campaigns. For all of these nations, war is an industry.

We demand for divestment and call for ceasefires, over and over and over again. We demand for intervention and separate the truth from the Zionist propaganda and misinformation that threatens its silence. And yet, America continues to back Israel’s war crimes. Why?

Because doing so aligns with America’s broader goal of preserving the power dynamics that enrich the Global North.

All of this brings me to a question that rips apart the moral envelope of “us versus them” and “good versus bad”: How far does condemning the system we live in—and play a part of—take us? And what does it mean to be a part of it to begin with?

If the central powers of the Global North (United States, United Kingdom, Israel, France, Spain, Portugal, Belgium, Netherlands, Germany, Italy…) benefit from and sustain colonial systems of oppression, this means that citizens of those countries—who exercise their international privilege—are connected to acts of violence around the globe. Take, for example, the supply chains that sustain American consumer lifestyles, maintained by a system where the Global South services the economic interests of the Global North via cheap labor and resources. Or the financial and military backing of states that use extreme violence against marginalized populations, which goes beyond Israel (see: the United States supplying over $54 billion in arms to Saudi Arabia and the UAE to support the war in Yemen, with tens of thousands of civilians killed and millions facing starvation) to maintain Western power structures (energy, trade, labor).

Even as ordinary, conscientious Americans, we are—by virtue of our consumption—implicit in global systems of oppression.

This is the point where I lay on the ground and stare into nothing, because the only thought left I have is: Okay…So what do we do?

While it may be naive to think that we can unpair ourselves from the colonial designs we live in, we can—as individuals—begin to approach, question and navigate the world from a decolonized perspective. If we are outraged by injustice, we must interrogate ourselves. It is imperative for individuals who benefit from systemic privilege (see: American and European nationals) to examine their own beliefs, biases and complicity in those systems that are, by nature, two-sided: where there is privilege, there is oppression.

Scholars of sociology like Walter Mignolo and Linda Tuhiwai Smith pose that decolonization begins with the rejection of Eurocentric philosophies that dominate the default understanding of the world. Embodying indigenous worldviews and the perspectives of those at the “border”, who have been marginalized by the power structures of the Global North, can train us to value the well-being of a community over sensational claims of terrorism used to justify its displacement. Reframing how we perceive the world is a vital step towards challenging it, which is a vital step towards changing it. Decolonial theorists like Frantz Fanon and Amilcar Cabral emphasize the importance of praxis—combining reflection with action. In applying what we learn from the process of decolonization to the real world (via vocalization, financial support and solidarity work), we can strive for something better.

I am still learning. Like a color book, every year I live, my comprehension of this world fills in a bit more. The fact that the authors above were unfamiliar to me until this year is emblematic of my ongoing education, something that I believe is core to the process of decolonization itself: in order to transform the systems we live in, we must learn to see them.

A system only functions if its parts operate in cohesion, if the machinery follows the design. Once we know the design, we can challenge it. Slow it down. Someday, rewrite it.

What is human nature? I think it is in our nature to want to know the truth, to wish for something better and to fight for what is moral over what is. It is also in our nature to become accustomed to things as they are. An affinity for inertia is, perhaps, the most frightening trend in the human condition. We let things happen. We forget.

Until we can’t anymore.

At that point, we fight.

My hope for the world is that we have the courage to fight: our biases, our systems, our disregard. To decolonize our minds. To challenge each other. To reject the customs of death and displacement that have become too normal for all of us.

“Never again” only means something if it is not said multiple times. ☷

With love,

Your favorite capybara ~ AKA Travis Zane