Is the World Falling Apart, or Do I Just Need to Delete TikTok?

Am I depressed, or is it just…?

It feels like the world is ending. There are videos of bombs in the sky, videos of mothers, brothers, boyfriends, wives, grandparents and children being disappeared illegally by civilian bounty hunters. There are videos of the US sending millions of dollars of military weaponry to join Israel’s campaign against Iran, despite failing to provide adequate healthcare, affordable housing, or meaningful disaster relief for communities devastated by wildfires, floods, and hurricanes. There are videos of us joking about what we would do if we were drafted into the US army (cunt walk, death drop, die). And there are videos of people trying an all bean diet for one month, because, even as the world is ending, we continue to invent new ways to torture ourselves.

On one hand, I understand that the vortex of TikTok is designed to make our inner thumbs spasm in hypnosis. Social media was engineered to capture our attention and hold it hostage. There are reports that the world is, in fact, better off than it was fifty years ago. There is less poverty. Higher child survival rates. But better does not equate good; better is not enough for the families who are losing their loved ones every single day to the black box of “detainment camps,” which are better described as concentration camps—over 4,700 people have been disappeared by ICE since Trump entered office. Better is certainly not enough for the people who have been disappeared themselves.

If one more person tells me to call my representative I am going to lose it. We have called our representatives, protested peacefully, donated to jail bonds, spoken out in public, reposted to the discourse of awareness and resources five million times, and still: the communities that have been marginalized since the founding of the United States continue to be targeted, disappeared, killed—fast by the hands of their neighbors, slow by the design of our institutions.

I am tired of writing these things. Of having to write to feel any sense of stability in the first place. We are the cells of the lungs of a smoker, the cells of the liver of a chronic alcoholic. The only way to change the behavior of the body is to fight back—or to end the body altogether. It feels like nationalism at large is in the midst of global decay. We are tired of decisions being made by men in wide offices who know little about what it means to live a real life, to feed a family, to cope and battle systems of oppression across class, race, gender, and sexuality. We are tired of certain men making the same men rich as the bones of populations pile up. Tired of seeing genocide play out like a reality TV show. Tired of arguing for the right to live: theirs, ours, everyone’s.

We spend so much time debating the rights of a nation to retaliate against another that we ignore the rights of a father, friend, or cousin to live. We have been sold the story that we belong to a nation, that those nations are held together by governments, when, in reality, we only belong to a nation until we are the ones being used as debt, we are only protected by a government until we are not, until we are deemed the enemy, which has recurred over and over and over again (slavery, Jim Crow, Native American “boarding schools,” Japanese American Internment, Lavender Scare, Operation Wetback, post 9-11 surveillance and detainment to Muslims, mass incarceration that disproportionately affects Black populations, ICE raids).

The reality is that we are—and always will be—the ones who lead the nation. We are the labor, the power, the economy, the future. So why are we not being heard? Why must we ask, over and over and over again, for our basic human rights.

Debating whether or not a nation as a state has the right to bomb another is, effectively, debating whether or not a politician has the right to mass murder civilians. These debates are futile. The problem is, and always will be, the gruesome mechanics of politics devised by those with legislative power. A nuclear threat was not the culprit for the 4.7+ million people killed in post-9-11 war conflicts. We are focused on the wrong threats. Remove the alcoholic from the body; remove the dictators from our nations. We are long overdue for a revolution, and yet, I cannot picture what revolution looks like.

In a time where the majority of us spend five hours on our phones, three hours in a relationship with a streaming service, and eight (or more) hours working to be able to afford the basics of modern life, it feels—to some extent—that revolution itself is yet another luxury that could only be afforded by generations prior. We protest, we speak out, we organize, and yet, at the end of the day, we continue to work for, and within, the systems we disagree with. We take breaks from social media and the all-hours news cycle in order to not only continue fighting, but continue living. Continue on.

This seems to be the online consensus, though: That America, at some point, will unravel like a poorly tied knot. That revolution—or perhaps just decay—is inevitable.

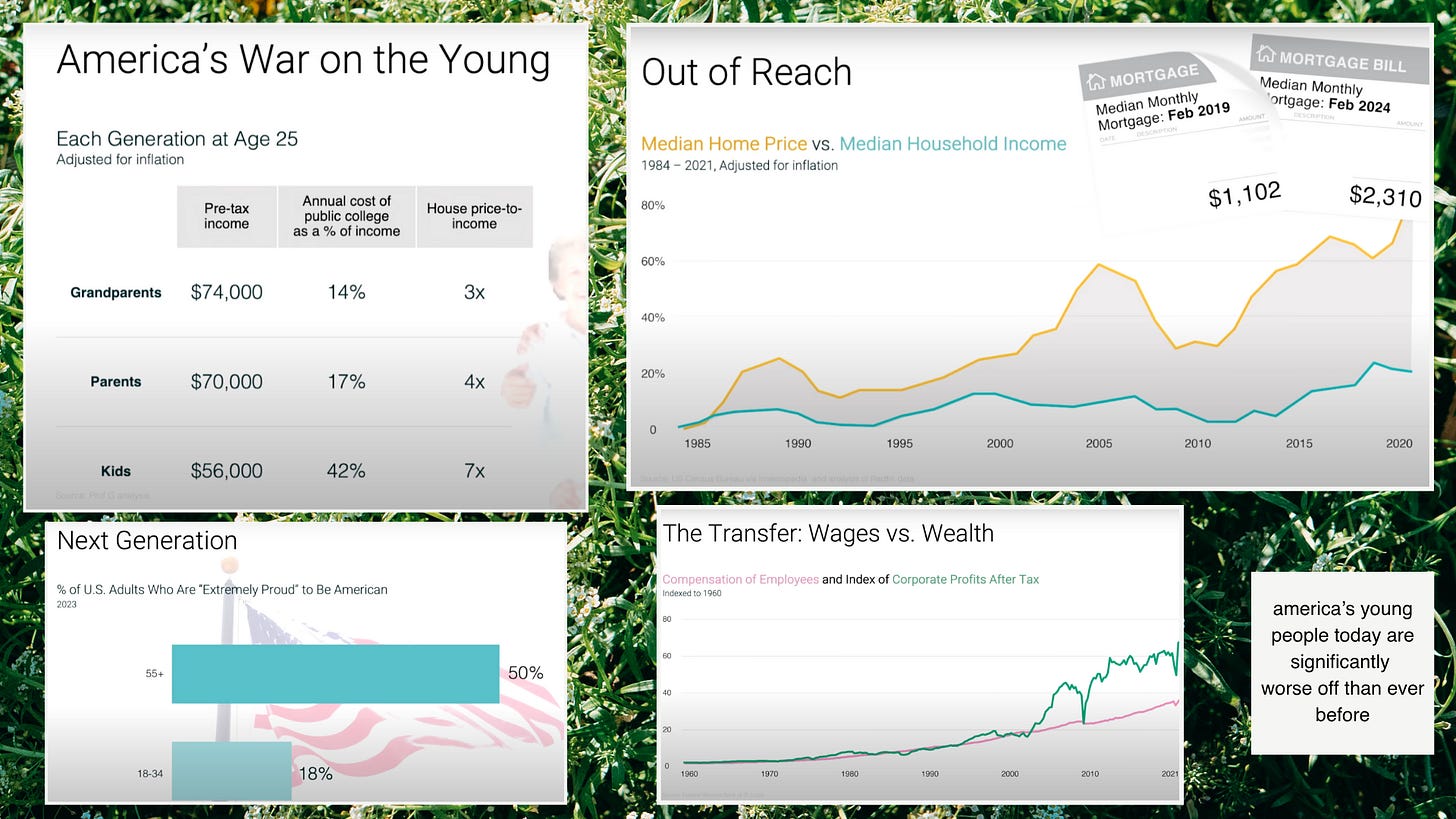

In a TED Talk that made me feel seen and defeated at once, an NYU professor assesses the greatest transfer of wealth in American history: from the young to the old. The talk details how young people today are significantly worse off than ever before—we have a surplus of technology to keep us entertained (or, some may argue, depressed) and a deficit of capital to keep us housed, fed, and capable of maintaining an upwardly mobile trajectory. The numbers speak for themselves.

A common theme I surface in therapy is a disillusionment with our modern societies: Israel’s genocide of Palestine that we have witnessed—and failed to alter the course of—over the past two years, Trump being voted into office, Trump’s war on: reproductive rights/DEI/LGBTQ rights/the climate crisis/people of color/immigrants/the working class, expanding mining across public lands, the frat culture of the ultra wealthy that feeds off of human violations, the growing death toll in the DRC and the world’s lack of interest in speaking about it…On one hand, we are hyperconnected to the realities of places we will never be and people we will never know, which often serves as the basis of the argument that we are unnaturally aware of what is going on in the world, which is why we are supposed to disconnect, turn off the news and set down the phone. On the other hand, it is only natural that we care about these things, because these things are not okay. These things are mothers and fathers and sisters, lovers and friends being erased in a matter of seconds by a missile. By an illegitimate claim that a people are less deserving than another when our DNA reads no different. It is only natural to want to know, to know and then be upset, for it is a lack of knowledge that ultimately leads to human death. If we are not disillusioned, not upset, not not okay, I would argue that we are fooling ourselves, turning a blind eye to what is actually happening. But is that all there is to be said: that the world is falling apart, and so we should fall apart as well?

The only good thing about the omnipresent algorithms of social media—which always seem to feed us the very things we’ve been talking, thinking, and writing about (via devices that always listen and see)—is that these same algorithms, at times and on the offhand, actually give us what we need. After a therapeutic week spent with my cousin, confiding in shared anxiety around the state of the world between sadistic jokes and mouthfuls of tacos, YouTube suddenly began recommending videos about the collapse of the United States, the rise and fall of American imperialism, and—most importantly—how to survive amidst the doom.

The conclusion we always come to is that we have a choice: we can let the doom of the world immobilize us or do what we do best—keep on living. The more I grow up, the more I am able to recognize that hope is a muscle we can train stronger, that joy is a language we can learn to speak, and that the gumption for living we so often yearn for, that we admire through the protagonists of novels and films, is not an enchanted disposition we are born with but a choice we must learn to make when we are faced with reality: a reality that is cruel, unfair, and unchanging. A reality that requires us to choose how to live: in woeful surrender or joyful resistance.

The problem with joyful resistance is that it sometimes feels impossible to see what is joyful about any of this. If hundreds of thousands of people are dying by the decisions of a few men, what is so good about this life, about humanity? And yet, achieving the impossible is innately human. It is human to defy the odds. The odds of a universe with life-supporting conditions is 1 in 10^120—a number so large we don’t have a category for it. It is in our nature—and a part of our survival instinct, a part of our resistance—to be an anomaly, to say: I am here, living in a pile of shit, and yet, there are beautiful things. Today I saw the sun filter through the leaves. Today I drank a glass of wine that reminded me of the strawberries my grandmother used to feed me in the summer. Today I did fifteen pull ups; last month I could only do eight.

This past weekend I slept in a warm bed. I hugged my partner with every ounce of force I had in me. I traveled with friends to the forest outside of Mexico City and ate soup inside of a restaurant beneath the pouring rain. We walked with wet socks, eyelids dusted in moisture, and inhaled the delicious air as if it were an offering from a supernatural source, and it might as well have been, because that is what we must see if we are to choose to live life: offerings here, offerings there, from the earth and from each other.

We talked about the world. We talked about nothing. Talked about going on a trip altogether, if not this month then the next, if not the next then the one after, if not the one after then the one after that. And in these small instances of living, the existential woe of what it means to be alive today dissipated into the background. The fact of the matter is that every person alive today is exactly that: living, showing up, doing it. Whether or not we feel like we know what we are doing has little meaning, for we are always doing it. We are here, and we are here together. And I think that is enough: to witness each other, to share our time, to choose hope over despair, to recognize that the choice itself is what makes the story of humankind worth something, no matter how poorly written it might be. To remind ourselves, over and over again: At least we are writing this part together. ☷

Thanks for reading Sleepover! In the spirit of accessibility, this newsletter will always be offered for free. Please consider a paid subscription if you’d like to support the things I create—with and beyond this project.

With love,

Your favorite capybara ☼ AKA Travis Zane