Death.

I do not understand death. When we die, where do we go? We ask this question as children, and rarely do the spaces between the words fill out, even as we grow into adulthood.

A few months ago, a friend I considered family, a friend I had spoken to only a few weeks prior, encouraging him to write again, agreeing to help him edit his thoughts towards coherency, a friend I expected to see in the future, demanded, even, despite the odds—for the echoes of his community confirming he would win, overcome, heal, seemed loud and large enough that they should come true—passed from cancer. We called him E.T., Edward, Ward. The last voice message he sent me on WhatsApp remained there, saved as unread, as if perpetuating its unopened nature would extend his life beyond the day he left. As if by keeping the words he sent to me unheard, it could be that they were never said, which meant, at some point, with the press of a triangular button, he could say them, I could hear him, and it could be that he is still here.

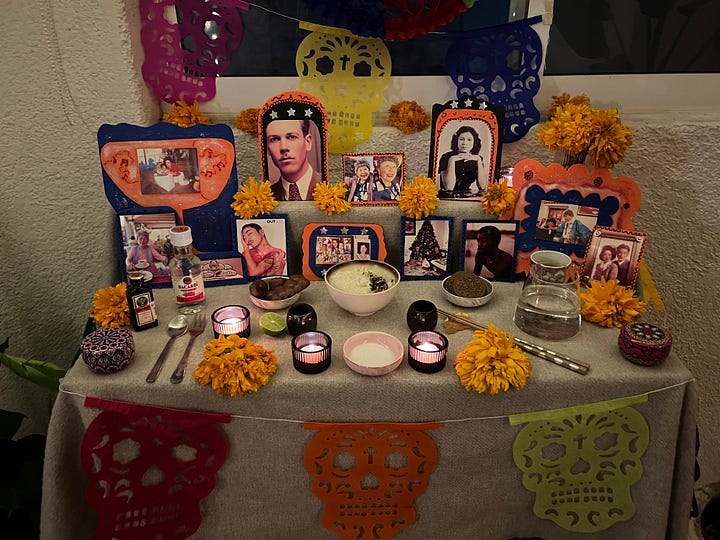

I added photos of E.T. to the altar my partner and I made for Dios de Los Muertos, alongside family members and friends who had passed in different years, some before I was born: my grandmothers, my grandfathers, uncles I had never met but heard many stories of, friends and family who had passed too soon—Moesi, Tomi, Lillian—too tragically, although to describe death like that makes me uneasy, for it assumes that the people who have passed on lost, that the living are the ones who continue to win. We lit candles, adorned the altar with favorite drinks and snacks, and surrounded their portraits with stained clumps of orange, the cempasuchil flower believed to act as a pathway for the dead, so as to offer them a chance to return, to enjoy, to embrace their loved ones. I like to believe in this idea, that the flowers are a path, that each and every person we honor returns as the best versions of themselves, new versions of themselves, unhindered by the expectations of a society or the limits of human life. My partner and I talked about each person we placed on the altar, what they enjoyed when they were here, what they might be doing upon their return. Who they might be growing into and all the ways in which they’ve evolved, no longer tied to the limits of the human mind, nor the distractions of the ego.

As I spoke about E.T. and looked at his photographs, a part of me felt that it was untrue, it could not be true. Somewhere, in some other dimension, in some other world, there was still a time yet to be had where we would run into each other, where we would laugh and hug and talk comedically about the woes of being queer, the hurdles of being Asian, wielding self-deprecation like a blanket stitched from the sun, sealing it around ourselves in a giggle as bright as the moon. I still don’t know if I know, if my body knows, if the part of me that exists between the neurons and vessels and organs knows. I know that I was told he is gone, and yet my mind still wonders: Where is gone? And how can I visit there?

In an attempt to encourage myself to process, I opened E.T.’s message and pressed play. His voice rang with texture, canny and particularly him, the way a saxophone is a saxophone, the way an instrument can take you back to your home, to your land, to a time in your life where all there was was the sound of it playing. I began to cry, listening to his timber, his pauses, his inflection, the generous use of girl, and thought to myself what I always think when I think about death: How is this possible? I understand the mechanics of it: Our heart stops, blood ceases its circulation, neurons fire their last signals. I understand its commonplace nature: Everyone dies. But it feels something beyond cruel, something beyond confusing, to accept that one person is no longer here and the rest of us are. That we will continue living, the world will continue as the world, and life will continue as life. It is almost as if I lack the language to understand it, as if it is something that transcends language itself.

Ever since my amah passed, grandma, Ah-Mah, Popo, Kwai Jin, Jeanette, I have had recurring dreams in which I see her again, in which I forget that she is gone, in which I remember that she is gone and then come to the conclusion that she has returned by some miracle or medical breakthrough, in which it feels so real that she is there with me and that I am holding her rice paper hands that the reality I belong to in the waking world loses its credibility, so far thinned as to shock me like a thunderbolt when it pulls me back to the other side. When I wake from these dreams, I wake sobbing, the part of myself that still does not know enough, that may never know enough “she is gone,” being scolded by reality and brought back to its terms: She is gone. You cannot hold her hand. You cannot hear her voice.

My partner says that these dreams are visits from my grandmother’s spirit, which is a belief I like to indulge in like cocoa when the clouds link arms and the trees lose shape. I also believe that it is the slow process of my consciousness beginning to understand that she, as the person I interacted with in this world, is gone. Perhaps both are true: In these dreams, her spirit is guiding me along the process of grief like a lighthouse in a storm. The last dream I had of her was the first dream I did not wake from crying, though I still felt the tears, somewhere, in my chest or on my temples. Perhaps they’d just learned to stay put.

In Buddhism, it is believed that death is not the end. There is the notion of rebirth, and of karma, both of which dictate that we are reborn into another form according to the actions, intentions, and attachments we exhibited in all our prior lives, collecting a calculation of energy that determines where we end up and how—as a human or an animal or a ghost, with preferential or unfortunate circumstances—but rebirth and karma itself are just two ideas birthed from a larger notion. The Buddhist belief that intrigues me the most is the notion that the beginning and the end, two clean mechanisms created by humans, do not exist. We view death with fear and discernment because it signals, in our minds, finality. Yet, if all matter is indestructible, then we existed before we were born, and we exist after we die. Death in the buddhist view is the end of a body, not a spirit nor a soul. We become attached to this life only because this is the limit of our knowledge.

I like the idea that life does not begin with birth, nor end with death. It makes sense to me: There is so much in this world that we do not understand. Why assume that we die with our bodies when we’ve yet to discern how, exactly, our bodies conjure our selves? I like the idea that there are things we do not know, that Buddhism does not know, that we will never know, and that the space the unknown lends us to imagine and create can serve as a shelter for grief and all of its parental forms—joy, love, longing—and where there is shelter there can be a home, a home we all belong to, no matter which part of life we are living: the figurative beginning, the figurative middle, the figurative end. Or, beyond.

I like to imagine new places, better places. Places where we can fly, form, dissolve, where the sweet clarity of the world–the nature of love and time, the way everything seems to soak over with light when we consider the power of both–nourishes us to the core of whatever it is we are, if anything at all.

Death, of course, still deepens the heartbeat and saturates our hours with an appetite for what can not be—another conversation, another day, another decade—regardless of how sweet and how far we imagine, for death feels unfair. I think about all of the people who have had their lives cut short by disease, by tragedy, by the white rage of an empire, and most of anything, it feels unfair. Unfair how life can be grouped into a number, a count, a historical statistic, squeezing all of the dreams and tears living entails by the hundreds of thousands, by the millions, into a handful of syllables: over 66,148 Palestinian civilians, as many as seven million indigenous American civilians, over 13,883 Ukrainian civilians, over 600,000 Armenian civilians, genocidally murdered by the IDF, European settlers, the Russian army, the Young Turks. Names that erase other names that will, too, in the end, be erased.

It feels unfair how time spills over us, how all of the lives that we have lost become a story. Even the ones that live to the end become stories, too. Time has no mercy for human nature and its tendency to pull towards meaning. Like iron sand around a magnet, we live in meaning as if it is eternal, creating it, sharing it, offering it, until it is not. It feels unfair that everyone was once a child, a youth, a wild thing searching for the roots with which we firm ourselves into adulthood, and if lucky enough to reach it, once those roots grew, a thing more calm, a thing more patient, watching the days roll by until the final bye was ours to give. Unfair that the world rushes on once we’ve said it.

The cruelty of human life is that none of us knows what lies ahead. We barely know what we are. On a recent walk in the city, a podcast chosen at random whispered a quote in my ear: When you fall off of a cliff, you can grab onto the rock falling next to you for comfort, but it will not change the outcome, it will not lessen the blow. I rarely think of life like this, but it is, isn’t it? We are all falling, attempting at flashes of certainty or will, and yet, nothing really is certain, nothing bends fully to our will. We come into this life with no knowledge of what it means to live, and then we learn. We learn that this is a spoon, this is a fire. We learn that people matter, that fighting for them matters, that enjoying them matters most. We learn that survival requires a certain suffering, though suffering is not all there is. We learn about joy and where it comes from. We learn about narrative and how it binds us, emboldens us, tears us apart. We learn how to unlearn the things we thought learning required, once seeing it as law that this is that and that is this, that the this and the that were not malleable, until the world itself appears malleable at its core, until we see that truth is a shapeshifter.

I hope we learn, most of all, that life is a freefall, that the best we can do is notice every detail as we plunge alongside the rest of the world. I hope we hug and kiss the rocks around us, dance with the light as it cascades by, and hold each other’s hands until our hands are no more, until the fall ends, turns into flight, becomes something else. ☷

Thanks for reading Sleepover! In the spirit of accessibility, this newsletter will always be offered for free. Please consider a paid subscription if you’d like to support the things I create—with and beyond this project.

With love,

Your favorite capybara ☼ AKA Travis Zane